Towards an Adaptive Organisational Culture

Feb 15, 2022

Written by Dr. Richard Claydon & Geoff Marlow | Image @bailey_i

As the world reverberates with the shock of the pandemic, business leaders are becoming more attuned to the importance of human behaviour within their organisations. Some employees have been more productive and engaged working from home than they ever were in the workplace. Others, notably women with young children, ethnic minorities, and people under the age of 25, have struggled with their wellbeing. This dispersed, hybrid workforce is also impacting organisational alignment.

The complexity of these challenges poses questions about what future leadership practices are required to ensure that organisations develop adaptive, future-ft cultures.

Why culture?

Although it has fallen in and out of fashion, culture has been the main organisational alignment tool for the past 40 years.

What type of culture is needed to enable high-performance hybridity and employee wellbeing, which also keeps organisations aligned and prevents unethical behaviour?

The Promise of Culture

We didn’t always think of organisations as having cultures. When Elliot Jaques introduced the concept in 1951, it was ignored. It didn’t grab anyone’s attention until the late 1970s.

At the time, US organisational systems seemed completely broken. Misalignment was rife, with many US companies experiencing huge tensions between strategy/finance, operations and development. Industrial action was rising. Innovative products were in short supply. Strategic thinking was painfully conservative. Drained of confidence, US leaders had no answer to the high-quality, cheap, market-impacting products coming out of Japan.

The US management consulting methodologies of the time had no solutions. Something completely different was required if these disparate elements were to be glued back together.

At the same time, McKinsey was looking to re-establish its intellectual dominance of the consulting market, which it had lost to Boston Consulting Group’s introduction of strategic consulting in the mid 1960s. Although it arrived almost by accident, culture seemed to be the answer. It melded three visions of organisation under a culture umbrella. This included Scandinavian and American flavours (McKinsey’s Operational Excellence team - Tom Peters and Robert Waterman) and a Japanese flavour (Art of Japanese Strategy team - Richard Pascale and Tom Athos).

- Japanese:

loyal operators playing a continuous development role - Scandinavian:

an egalitarian workforce incorporating diverse voices - American:

the pre-existing hard Ss of Structure, Systems and Strategy common to US organisations, and Peters and Waterman’s eight principles of operational excellence

These insights combined into the Soft Ss (Staff, Style, Skills) of McKinsey’s soon to be famous 7S model.

Initially, the hard and soft Ss were glued together by Athos’s concept of Superordinate Goals, which are goals that are worth completing but which require two or more social groups to cooperatively achieve.

It quickly became clear that this wasn’t catchy enough. A different S was needed. Over a two-day meeting, McKinsey came up with Shared Values. Soon, the idea that the shared values of strong cultures were central to organisational success became embedded in the management lexicon.

Over time, three cultural modes developed.

- Consulting: Designed cultures, in which consultants work with executives to determine which value-set best matches their organisation and industry type, and then transforms the organisation accordingly.

- High-tech: Organic cultures common to start-ups and high-tech organisations, which emphasize, to an extraordinary degree, creativity, freedom, responsibility, openness, commitment to truth, and having fun.

- Evangelical: The source of the belief in and problem of strongly shared values, in which cultures begin with huge energy, dynamism and commitment, before inevitably sliding towards totalizing fundamentalist forms that internally destroy an organisation.

The combination of McKinsey’s drive to regain the intellectual dominance of the consulting market via the 7S model, the emergence of an exciting American high-tech version of organisational culture, and the rapid improvement in the US economy under evangelical favourite Ronald Reagan, ensured the success of “strong culture''. This was tested in the dotcom crash, in which many strong culture high-tech superstars failed. As a consequence, research into the efficacy of organisational culture pretty much ceased.

Now that alignment is once again a problem, leaders are turning back to culture as a behavioural lever for COVID-impacted, hybrid work. This decision needs to be informed by the promises and risks inherent to this approach.

The Complexity of Culture

The culture movement of the 80s and 90s delivered a new organisational language. The hard number-driven approach of US consultants was replaced by a “soft and fuzzy” linguistic turn in which evocative language and colourful stories, and how they impacted the heart and soul of employees, became central to organisational alignment.

While the cultural school initially came out on top, over time numbers and stats won out. The richness of the linguistic-cultural model has been undone by a renewed focus on fit, measured behaviour, and compliance. This has drained the culture movement of its energy and created a paradox for those trying to ensure fit while delivering diversity.

Other tensions have also become apparent.

- Human Bias: In a compelling critique, Phil Rosenzweig points out that two-thirds of the companies identified as operationally excellent in Peters and Waterman’s research slumped in market performance. He wonders how “so many companies, selected precisely because of their strong values and discipline and culture and focus, could all falter so quickly.” Ruling out an ironic outcome, in which the excellent companies become victims of complacency or self-satisfaction precisely because they were chosen, Rosenzweig suggests the findings were infected with the biases of the managers interviewed, who reported that the culture was great simply because the company was doing well.

- Small v Big: A nine-year longitudinal study at Stanford illustrates how start-ups with strong, high-commitment cultures nearly always survive bad times, whereas those focusing on hiring people with great technical or managerial skills, but little cultural passion, tend to fail. In contrast, high-commitment hiring and passion for the culture in large, complex, established companies was predictive of poor profitability and low growth.

- Anti-Leadership Development: There is extensive evidence that while strong cultures might be extremely attractive to younger employees trying to find their place in the world, they don’t attract people trying to develop their leadership capacity. Younger people tend to pay great attention to the ideas, norms and beliefs of the people and systems around them, and are motivated to fit in. Consequently, they find a strong culture very attractive. However, as people develop, they become far less defined by other people, their relationships or the environment, and instead begin to feel constrained by strong cultures. The more they display emerging characteristics of leadership, the more likely they will be judged as failing to fit.

Developed employees tend to have the following reactions when observing the gap between the simple cultural rhetoric and the complex cultural reality.

- Cynicism - disgust at the gap

- Apathy - despair at the gap

- Irony - wry, even joyous, recognition of the gap

This is not evidence of disengagement, but the inevitable impact of trying to design a simple set of core values that everyone will share in a complex and diverse organisational environment. It is an impossible task because such a set cannot reflect the far more complex lived experience of every employee.

In exploring this complexity, the most robust analyses of culture illustrate how three perspectives co-exist within the cultural whole.

- Integrated - an aspirational value-set that people can be inspired to work towards, but can never actually achieve.

- Differentiated - inevitable sub-cultural interpretations that occur in different teams, departments and countries as people make sense of the value-set within the context of their own work.

- Ambiguous - individual contestations and disagreements about what the value-set means informed by professional pride and personal histories.

In large, complex, established organisations, all three of these dynamically interact. At times, people will be inspired by the aspirational value-set. At other times, their group’s sub-cultural interpretation bonds them. Sometimes, people will be inspired by holding different opinions and the space in which to discuss and explore them.

The key to enabling such multi-faceted inspiration lies in the practice of culture. This, too, has three dimensions.

- Managerial - everyone who doesn’t fit is a bad apple who should be retrained or fired.

- Radical - the culture isn’t delivering. Transform it.

- Adaptive - dynamic multiplicity is inevitable and value creating if transformed into strategic opportunities.

Adaptive practice is already central to high performance teamwork. The Agile Method facilitates dynamic and diverse sense-making in teams. Psychological safety enables contestations and disagreements to surface without fear and anxiety. Research indicates that teams that master these practices become 60% more productive and 60% more responsive to customer input. Culture has not caught up. The gap is clear, with 70% of these high performing teams reporting increased tensions between them and management.

For a culture to be fit for purpose in digitally transformed hybrid workforces, it has to enable this adaptive agility across the organisation.

The Future of Culture

Teamwork has been dramatically reimagined over the last twenty years. The same cannot be said for culture. As COVID illustrates, the world is becoming increasingly unpredictable. The pace, complexity and volatility of change means that there simply isn’t time for information, data and insights to work their way up a hierarchy, be explored, debated, developed into plans and rolled out before the world has moved on and rendered them obsolete.

Adaptive cultures occur where the sense-making, decision-making and action-taking inherent to high performing teams become tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded, and widely distributed throughout the organisation.

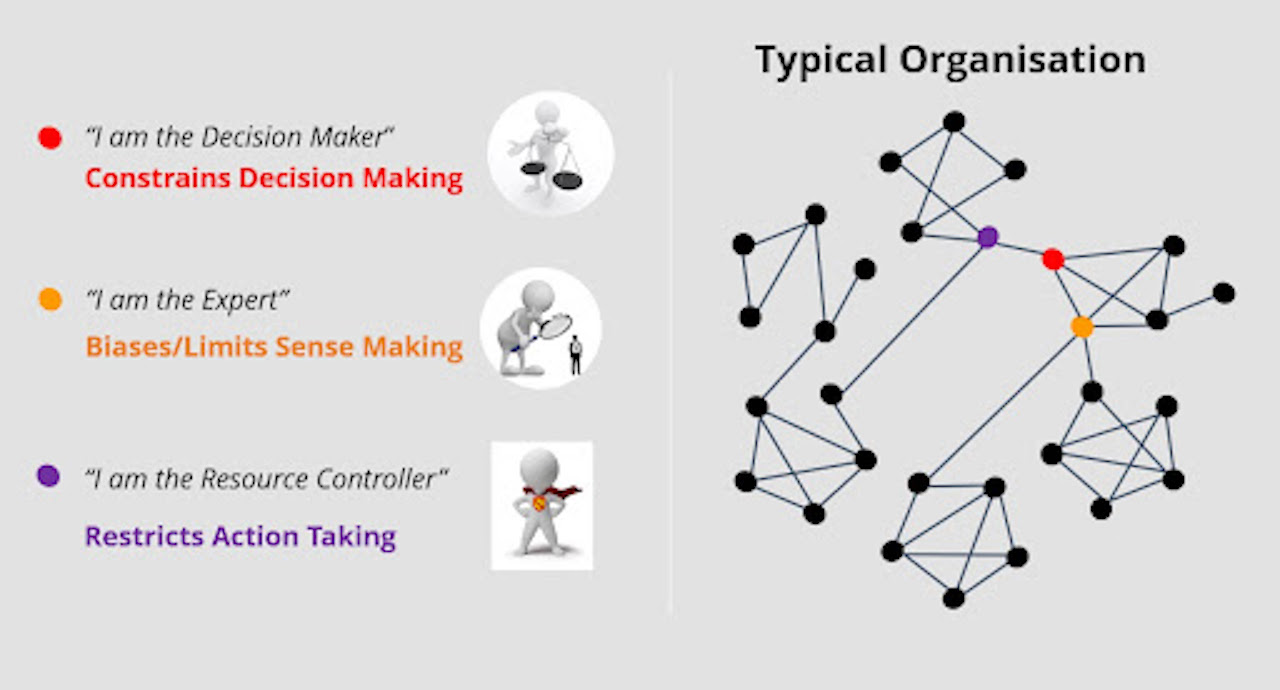

Figure 1 - Value creation networks with a) wide bridges - the ‘fishnet’ form on the left, and b) network bridging constraints due to the impact of key influencer mindsets on the right.

Startups automatically generate this kind of culture by building wide bridges of multiple linkages of cross-functional interconnections across the value-creating network. These encourage collective sense-making, decision-making and action-taking to naturally emerge, flourish and evolve.

As Figure One illustrates, while it is natural for this kind of culture to emerge in startups, it gets smothered, stifled and strangled in larger established organisations. This is because of a small number of key influencers. These are not necessarily people in the most senior positions but those whose mindsets, attitudes and behaviours have far-reaching systemic effects on the organisation’s culture.

Figure 2 - Value creation networks constrained by narrow key influencer mindsets

Adaptive cultures only flourish if these key influencers enable rather than block sense-making, decision-making and action-taking. Damon Centola’s research on cultural transformation shows that the complex contagion of new mindsets, attitudes and behaviours of a future-fit, adaptive culture only propagate when people encounter repeated reinforcements from many people in their network of value-creating relationships. This cannot happen if key influencers perform a blocking function that prevents this type of interaction.

Figure 2 shows three common key influencer mindsets that collapse the fishnet, forcing multiple network connections to ‘go through them’, thus creating narrow bridges.

“I am the decision maker”:

- Creates a decision bottleneck by dominating and distorting the network

- Generates self-imposed stress for the ‘decision makers’

- Results in poor quality decisions due to overload and fragmented attention

“I am the expert”:

- Distorts, dominates and impoverishes organisational sense-making

- Vastly curtails the capacity for the emergence of new ideas

- Contributes to poor quality decisions due to biased and patchy sense making

“I am the Resource Controller”:

- Constrains the availability of required resources by saying ‘no’ too often

- Prevents people from taking the actions necessary to create value and flush out sense making insights

When key influencers are helped to broaden their mindsets, they no longer constrain the emergence of the wide bridges at the heart of an adaptive, future-fit culture.

Wide bridges are the foundation for the tightly coupled, embedded, distributed, iterative sense-making, decision-making and action-taking required for the organisation to thrive in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world.

Wide bridges will ensure those working from home are just as much part of meaningful organisational dialogues as those working in the office. Active, wide scale involvement in sense-making will bring wellbeing benefits, as employees will a) be protected from social isolation by these ongoing and meaningful dialogues, and b) find agency and purpose in their activities, which massively correlate with wellbeing.

Finally, wide bridges lead to greater openness and transparency of communication, which ensures that unethical conduct is far less likely to take root and spread.

---

Authors

Dr Richard Claydon is the Chief Cognitive Officer of EQ Lab, an extended intelligence laboratory and cognitive gym accelerating people’s abilities in the behavioural dimensions of future-ready work at scale. He designed and teaches the leadership module for Macquarie Business School’s future-focused Global MBA (ranked #6 worldwide by CEO Magazine).

Geoff Marlow is an EQ Lab Global Faculty member with 35 years’ experience helping organisations throughout Europe, Asia and the US to create future-fit cultures. He has served on the Global Leadership Team of Peter Senge’s Society for Organisational Learning and with former UK Foreign Secretary Lord Owen on the board of anti-hubris charity The Daedalus Trust.

This article has been adapted from the Adaptive cultures: Enabling high-performance hybridity and employee wellbeing article published by the Governance Institute of Australia to support the Culture is a Risk presentation t their annual conference.